…poses a hot question

by Rivkah Roth DO DNM

The lure of an adrenaline rush and sharing social time away from home and amid a group of common goal- or challenge sharing co-riders is always tempting.

Unfortunately, such weekend clinics often end up overriding what is good for a horse and/or its rider and lead to frustration afterwards when riding actually has become more difficult, or a horse appears soured.

Therefore, to attend a clinic or not to attend a clinic is a question that should be weighed carefully. An impulse-free decision depends on various factors.

Broadly speaking there are two types of clinics.

- Where the clinician watches what you are doing and then makes suggestions on how you can make things easier for you and your type of a horse.

- Where the clinician teaches something new or different without being interested in what you have done so far with your horse, or what your horse is built for.

Clinics of the 1st Type

The first type of clinics tends to be facilitated by international caliber clinicians who have trained many rider/horse teams from the beginning stages to the top levels. They often pick their attendees via auditioning tapes according to where they believe they can make most difference in the given short time.

It’s this simple!

Teaching styles differ. Some clinicians are approachable; others less so.

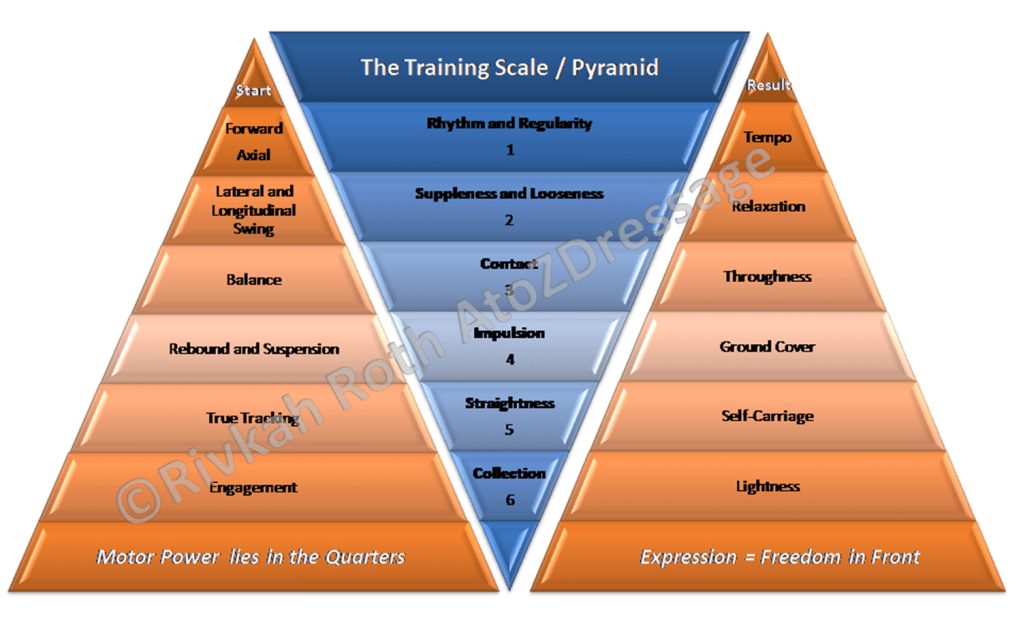

Yet the best of them guide each rider/horse pair back through the basic precepts of the Training Scale.

- First and foremost, this requires a steady and constant Rhythm — the longitudinal component;

- Suppleness, the freely swinging back and trunk in unrestrained forward movement — the lateral component;

- and an elastic Contact –creating the basis for the next steps.

Without these three and a good dose of natural Impulsion (to get the horse to move as freely under rider as it does at liberty), there can be no even muscle development (what we understand as Straightness — which, just to make this clear, is not a straight spine of the horse, but its even left vs. right development!). And without all of these in place, there is zero justification for Collection (the collecting of the quarters forward towards the rider’s and horse’s centre of gravity).

Try to attend many of these clinics as a spectator. You will often gain more insights than the riders who may simply be used as “demos” while the clinician explains concepts to the usually large number of spectators.

Stay away from recently turned competition riders who made it into the FEI ranks on one or two (mostly already trained horses) but without having produced students into the upper ranks. It is rare not to find a hand-riding front-to-back teaching (manipulating in the truest sense of the word) style among them.

After good work, the horse happily goes forward with greater ease and willingness.

Clinics of the 2nd Type

The second type of clinics is more common. It is, unfortunately, also more destructive on mind and body of a horse, and its relationship with its rider or handler.

Few of these clinicians have turned out riders and horses to the top levels. They mostly fuddle along at home and in the circles of their all-admiring clientele.

These clinics often promote a singular topic or a singular “virtue.” So, for instance, such a facilitator will always reach for the same remedy, or even build an entire weekend around dragging a horse from one leg-yield to another.

Therefore, in most of these cases, unless you have a stocky Quarterhorse or a compact Iberian with an angel’s patience, you might at most want to go watch such a clinic as a spectator.

Educate your Eye

Watch for tail carriage and facial signs, interactions between horse and handler, ear positions (in different directions), eye directions (back or down), lower jaw pushing forward or pulling back, etc., etc.

Positive:

The horse’s connective tissue feels and looks springy and vibrant.

The horse’s alertness level has increased, while it proudly oozes an inner calm.

During good work we always expect to see an active increase in joint action in the horse’s quarters, not as a response to a whip or other touch, but literally driven by the horse’s inner motor.

Negative:

A quick gentle stroke of the neck and abdominal muscles reveals a dull or tight feel of the connective tissue.

The neck/topline may appear more weedy. — The horse has relinquished itself to its fate so to speak, or in other words, has shut down.

After negative work, the horse takes on a submissive stance, eyes focus down (no, that is not relaxation).

In the negative outcome, it then is no surprise, that the hind toes start to drag, and one or all of the joints e.g. lumbars, sacrum, buttock, stifle, hock, fetlocks is blocking (driving up the quarters — with a line visualized between buttocks and mouth aiming downhill).

A single blocked joint will furthermore drive the hindleg out to the side resulting in a toddler-in-full-diapers gait (see my sketches above), or across the horse’s midline into the track of the opposite side. The latter may look “super” but the horse then almost always will not want to move freely forward, cannot bend its spine according to the track through a corner or on a circle; or it starts running through the rider’s seat and hands.

The good clinician only works back-to-front by…

- allowing or encouraging the hindfeet deeper under the joint centre of gravity (on a line perpendicular to the ground dropped from the stirrup bars).

The hindlegs then come closer together to carry the horse in an uphill fashion; they never spread wider.

To indicate positive back-to-front work, forelegs must land where the horse’s nose points (on or in front of the vertical).

As a result, the horse’s gait opens up and becomes more rhythmical and free.

Any decrease in joint activity will confirm that an exercise is not conducive to creating improvements.

Watch for negative excess joint action in the forehand (often a sign of front-to-back work)

- Over-active joint flexion in elbows and knees may indicate dropped withers and blocked shoulders. Not a positive sign.

- Negative also are a trigger-finger-like flexing of the fetlocks with their horseshoes pointing up towards the horse’s girth.

As a result, the horse shows flailing forelegs, or slows down its movement to a near-standstill. The movement is no longer coordinated, and the rhythm is broken.

It lacks biomechanical and physiological sense whenever, as is the case in many openly accessible clinics, movement is directed to imbalance the horse laterally by pushing it to abduct hindlegs or shoulders. For instance, under saddle or in-hand pushing a horse through endless leg-yields and other lateral moves does nothing but throw the horse more on its forehand.

Despite widespread claims, this approach neither creates lateral nor longitudinal suppleness, throughness, or strength. A horse simply is not build to abduct its legs in a splits-like movement. Any lateral movement has to come out of an adduction followed by a subsequent “catch-up”phase.

These problems can best be detected by looking for the horse’s toe mid-line. A rigid horse points its toe-midlines in different directions. The balanced horse will point its toes in one-and-the-same direction.

Always remember that suppleness requires supple, elastically flexing joints and increasing/controlled rebound power through fetlocks, hocks, stifle, buttock, sacrum, and lumbars.

- This is impossible with slowed-down work where the horse literally does not get off the spot.

- The longer the horse’s weight-bearing stance lasts, the less supple a horse tends to be.

Useful riding coordinates the horses footfall.

Potentially damaging work disassembles the horse’s footfall.

Undesired Physical Outcomes

Sadly, frequently I have noticed in such horses malalignments in their C7/T1 area of their spine (drop in the shoulder sling) resulting in slanted withers (unilateral weight-bearing often promoted by heavy-handed handlers – of course not on purpose, and mostly on the left), along with opposite stifle pathologies (laterally slipped femurs).

Over a few decades I have seen a significant number of horses whose owners attempted in-hand and under-saddle approaches (often because they lack the ability to sit and follow their horses big, natural movement).

The resulting mental shut-down in these horses is nearly always predictable. Instead of the handlers paying full attention to the horse in a foreign environment, he focuses on the clinician. The horse cannot understand why it gets pulled and prodded by a rider who is not “present” and not reading the horse, just its legs.

The Answer to the Conundrum

So, how do we know if a clinic is worth attending or not? Simple answer: always go attend first as a spectator, and put on your sharpest glasses.

Everything must make sense.

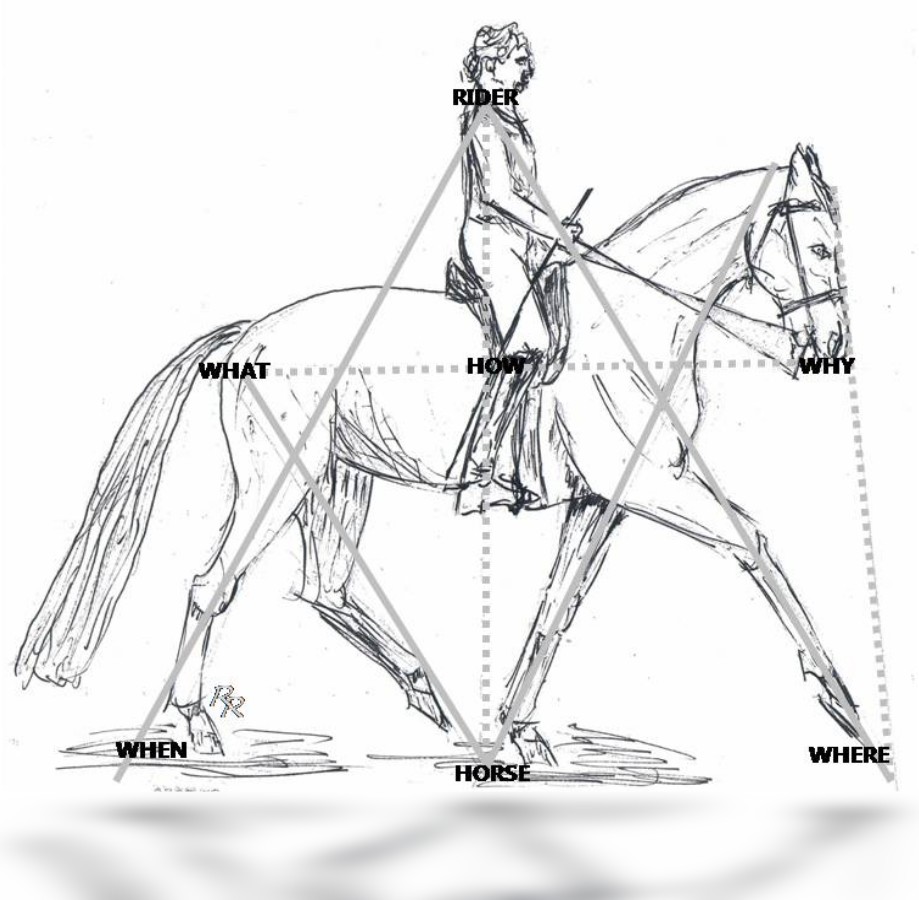

Get answers…

- not solely on the what

- and where,

- but also on the why

- and the how

- and when.

And when you have received answers, go question each of these answers again, until you fully understand he implications of any one single action or request.

This is what Clinics are for!

Last but not least, consider the trust component between you and your horse. Going to an unfamiliar place is fine if the rider connects with the horse like at home, or draws even closer to his horse (physically, mentally, and emotionally).

However, in most scenarios, at a clinic the rider is not at all present for his horse. Instead, all of his attention focuses on the clinician, the spectators, his friends, and what to “do.”

The horse then becomes an object “to do things with” or to “make do things” rather than forging a deeper partnership by discovering how two bodies can interact with greater ease.

Make a Point to Look at this from your Horse’s Angle!

If then the rider also does entirely different exercises than at home the horse easily gets confused. And, if the rider asks for all sorts of contortions from the horse (insecure always, because the rider “is just learning…), and these contortions make the horse’s body feel uncomfortable (such as a leg-yield achieved by doing the splits rather than by a crossing over), how can your horse’s confidence and trust in you not be shaken?

It can be a long road back to repairing a trust shaken by such an outing. Therefore, do not give in to impulse-dives into the clinic world. Think about this carefully, and first attend as a spectator (should your curiosity just have to kill the cat).

For further reading: first published 2021-06-21 on coachmetoo in response to having to treat several horses after such a clinic, I recently transferred that blog to my AtoZDressage website: Collection

copyright Rivkah Roth DO DNM

Rivkah Roth, author of the reference handbook and teaching manual, “A to Z Insights for Riders, Trainers, and Coaches — Old and New Dressage Concepts and Questions,” is the founder of Equiopathy and a natural health practitioner, lecturer and author with over six decades in the saddle as a correction rider (Swiss National License LMS since 1968) and many hours as a National Grand Prix and FEI C dressage judge.

The achievements of her former and present students and mentees include professional coaches on 5 continents (incl. CDN/EC I to III, ISR I to III, Dutch 3rd Level Instructor, USA, AUS), 1986 Dressage World Championships alternate (CDN), 1986 National GP Kuer Champion (CDN), 1992 Barcelona Olympics Longlist 3-Day (CDN), 2002 Young Horse Dressage World Championships – Verden/GER (ISR), World Cup and WEG dressage horse (CDN), many National and Provincial Champions on all levels (CDN / ISR / SUI).